Payments After a Warrant of Removal in New Jersey

Once a Warrant of Removal is filed, landlords must accept only full payment of all arrears. Accepting a partial payment at this stage can give the tenant an argument that the landlord waived the eviction.

For Property Management:

• Do not accept any payments unless they satisfy the entire balance.

• If a payment is received, send written notice immediately: “Although received, the payment is not accepted. It is being held in escrow pending clarification of the legal status of this matter.”

• You may also return all payments outright unless they cover the full arrears.

Clear steps protect the eviction and avoid unnecessary delays.

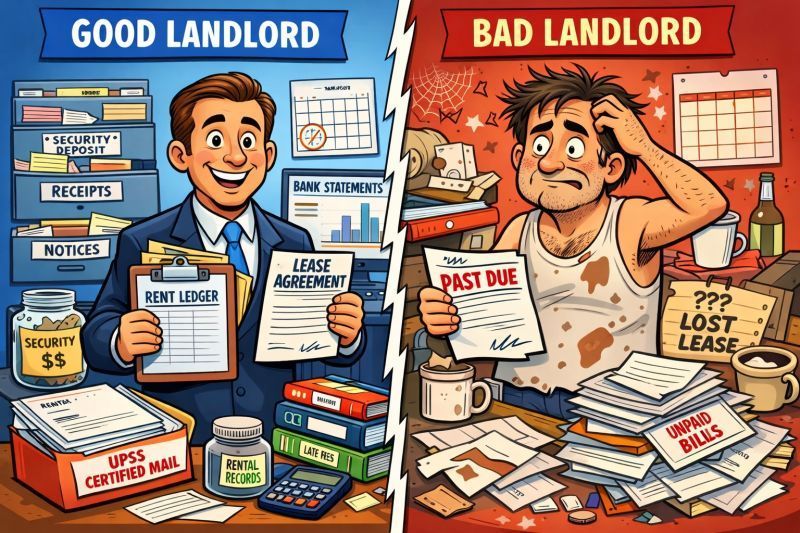

Eviction vs. ejectment com1) Understands that a lease ending does not create eviction rights. Under the New Jersey Anti-Eviction Act, N.J.S.A. 2A:18-61.1 et seq., a landlord generally cannot evict a residential tenant simply because the lease term expired. Statutory good cause is required. 2) Defines “Additional Rent” in the lease. All charges beyond base rent, including late fees, utilities, legal fees, and repairs, are clearly labeled as Additional Rent so they are enforceable in an eviction hearing. 3) Gives the security deposit notice on time. Within 30 days of receipt, the tenant is told where the deposit is held and the annual interest rate, with annual interest notices thereafter. Best practice is to have it in the lease itself. 4) Accounts for the security deposit promptly. Within 30 days after move-out, the landlord sends either the full refund or an itemized list of deductions with the balance. 5) Sends an abandoned property notice when applicable. If a tenant leaves property behind, the landlord sends a proper abandoned property notice and holds the items for at least 30 days before disposal. 6) Maintains clear, court-ready documentation. An accurate rent ledger, all notices dated, and proof of service preserved, including USPS mailing records. Following these practices puts a landlord or property manager in a much stronger position if a case goes to court.

Eviction vs. ejectment comes down to one threshold question: is the occupant a tenant? An eviction applies only where a landlord-tenant relationship exists. Because tenants receive heightened statutory protections, these cases must be brought in Landlord-Tenant Court and proceed as summary actions limited to possession. An ejectment applies where no landlord-tenant relationship exists. These matters are typically brought in the Special Civil Part (DC docket) or addressed in the Foreclosure Docket, most commonly when a former owner remains in possession after foreclosure or a failed sale. Filing the wrong action means delay, dismissal, and unnecessary cost. Everything starts with one question: tenant or not.

A time of the essence notice is a written notice used in New York real estate transactions to turn a flexible closing date into a firm deadline. After the original closing date passes, either party may do so by giving notice that is “clear, distinct, and unequivocal” (ADC Orange, Inc. v. Coyote Acres, Inc., 7 N.Y.3d 484, 824 N.Y.S.2d 192 (2006)). The notice must “fix a definite and reasonable time for performance” and “clearly inform the other party that failure to perform by the stated date will be deemed a default” (Malley v. Malley, 51 A.D.3d 1088, 861 N.Y.S.2d 149 (3d Dep’t 2008)). It must also specify the date, time, and place for performance and warn of default upon nonperformance (Bardel v. Tsoukas, 303 A.D.2d 344, 755 N.Y.S.2d 648 (2d Dep’t 2003)). Whether the deadline is reasonable depends on the facts and circumstances, including good faith, prior conduct, and potential prejudice (Zev v. Merman, 73 N.Y.2d 781, 536 N.Y.S.2d 739 (1988)).

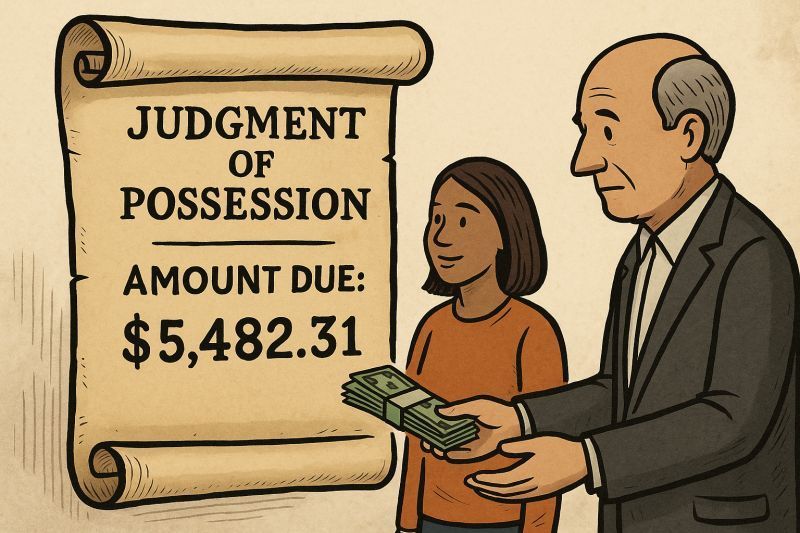

A major published decision just reshaped how New Jersey handles last-minute rent payments under the Stack Amendment. In Fairkings Partners, LLC v. Essence L. Daniels, the Appellate Division ruled that a tenant only needs to pay the amount listed in the Judgment of Possession to stop an eviction, not any additional rent that accrued afterward. If a landlord wants the extra rent, they must file a separate action.

In most commercial real estate deals, the buyer and seller each make certain promises about themselves and the property. These promises are called representations and warranties. They are basically statements saying, “Here’s what we’re telling you is true about the deal.” These statements help both sides feel comfortable moving forward. They also create a clear record of the important facts everyone relied on when signing the contract. If something later turns out not to be true, the other side may be able to make a claim or get compensated. -They also help divide the risk between the parties. In simple terms, they: -Show who is responsible if certain things go wrong. -Allow a party to bring a claim if a promise was false. -Trigger any obligations to reimburse or protect the other party. Because of this, both buyers and sellers care a lot about what representations and warranties say, they’re a key part of making sure the deal is fair and protected.

Landlords often ask: “Do I need proof the tenant actually got the notice to cease?” The answer is......not exactly. Under New Jersey law, a notice to cease just needs to be served in a reasonable way. You don’t have to prove the tenant actually received it. (N.J.S.A. 2A:18-61.2; Ivy Hill Park Apartments v. Abutidze, 371 N.J. Super. 103.) But when it comes to a notice to quit and demand for possession, the rules are much stricter. The Anti-Eviction Act says it must be served by one of these methods: -Hand delivery to the tenant or another person in possession; -Leaving it at the home with a family member over age 14; or - Certified mail (and if unclaimed, send regular mail too). You don’t need proof the tenant opened the certified letter, mailing it properly is enough. Best practice: Serve both the notice to cease and the notice to quit the same way, ideally by personal delivery or certified and regular mail. It’s the easiest way to avoid any “bad notice” defenses later. (A.P. Dev. Corp. v. Band, 113 N.J. 485, 495 (1988).)

Show me a lawyer who isn’t at least a little anxious, and I’ll show you a bad lawyer. A lawyer’s main job is responsibility; to the client, to the facts, and to the law. If you truly carry that weight, you’ll feel it. That edge of nervous energy means you care enough to be careful, to prepare, and to get it right. Confidence is good. Responsibility is better.

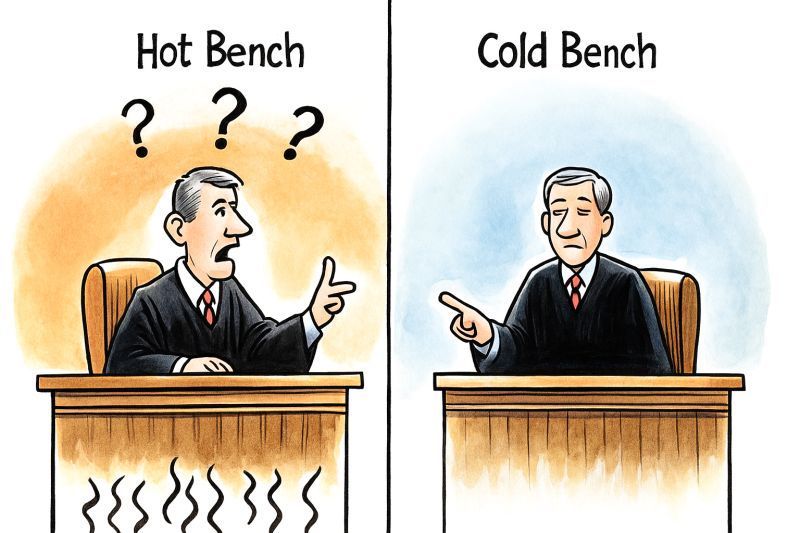

Some judges ask tons of questions during a hearing, lawyers call that a “hot bench.” It can feel intense, but it usually means the judge is engaged and wants to really understand the case. Other times, a judge barely says a word, that’s a “cold bench.” It doesn’t mean they’re uninterested; it just means they prefer to listen quietly before deciding. Good lawyers have to adapt to both: answering rapid-fire questions with composure on a hot bench, and keeping things interesting and clear on a cold one. Either way, the goal is the same, help the court see why your client should win.

We’ve recently observed that landlord-tenant trial dates are being scheduled quicker than before — often within 5 to 6 weeks of filing. We believe this is connected to the New Jersey Supreme Court’s amendment to Rule 6:2-1, which now requires trial dates to be noticed 21 days after service of the summons (rather than five weeks). The updated summons (Appendix XI-B) must also list the trial date, time, and location. It looks like the courts are already beginning to implement this change in practice.